The Wizdish Rovr VR treadmill being used in a gym. Photo credit: Wizdish

Vincent Van Gogh sat up three nights in the fall season of 1988 to paint The Night Cafe – an all-night haunt for down-and-outs in a southern French town. Now a virtual reality game lets you go into the painting and move around for a closer look at objects from different angles.

Most people would do this by wearing headsets while seated or standing. This can cause motion sickness after a while because of a mismatch between what you’re seeing through the headset and what your body is experiencing in its relatively static state. And this is one reason for VR failing to live up to its promise.

Hundreds of millions of dollars has gone into trying to replicate walking in VR. What we’ve done is to simulate walking by sliding.

My experience of wandering into Van Gogh’s world of vivid colors was more realistic because I had to move my feet to go towards an object, such as ambling across to the pianist in a corner and peering over his shoulder.

I was on a VR treadmill on display at the Startup Festival in Seoul. I had handrails for support and wore headsets. But it’s the pair of shoes I wore that was really unique.

The shoes were made of a special material that enabled them to slide with minimal friction on the treadmill, which acted more like the trackpad of a mouse. Sensors picked up the sliding motion of the shoes to let me move towards any object I saw in the painting. After a while, I felt like I was walking, even though I was actually slip-sliding about.

To slide and not to take steps makes a big difference, explains Charles King, CEO and co-founder of Wizdish, maker of the Rovr VR treadmill I tried out. “Hundreds of millions of dollars of effort has gone into trying to replicate walking in virtual reality. What we’ve tried to do is to simulate walking by sliding.”

Why slide and not walk

Walking involves lifting a foot for the next step. And that requires balancing momentarily on one foot, which is an unstable state. That’s why we topple over as toddlers before we learn how to balance ourselves while walking.

A visitor to the Startup Festival in Seoul tries out the Wizdish Rovr VR treadmill. Photo credit: Tech in Asia

There are VR treadmills that mimic walking, like the Kat Walk made by Chinese startup KatVR which raised US$149,278 on Kickstarter in 2015. It created new mobility to make VR more realistic and counter the problem of motion sickness. But because walking with special shoes on a treadmill is unstable, Kat Walk requires a bulky contraption with a harness going around the waist and crotch to prevent users from falling.

Hence the idea of sliding to simulate walking – and Wizdish has a US patent for its implementation. It aims to provide stability without the need for a harness. This enables a lighter-weight ensemble and a less intrusive experience than being strapped to a harness.

After a few minutes of sliding about in the Van Gogh painting, I only needed to place my hands on the circular handrail for reassurance rather than support. Knowing that I was sliding on the same spot also took away the fear of bumping into something while I “walked” with a VR headset strapped on. At the same time, my brain got cues from my feet that I was moving and related it to what I was seeing in the headset.

“What VR needs is some sort of physicality. And that’s what we supply because if we had done all that walking around whilst we were seated in a VR environment, it would not have felt real,” explains King.

A mouse for VR

King likens the Wizdish Rovr to the trackpad of a mouse for a PC, and hopes this will have a similar effect on navigating VR worlds. But of course, VR mice – like the Rovr shoes – are far more complex, involving neuroscience and materials tech. It’s also an expensive proposition for homes or personal use, at least for now.

Wizdish co-founder Julian Williams shows the Rovr shoe with sensors on the sole to a visitor at the Startup Festival. Photo credit: Tech in Asia

The Rovr ensemble costs US$950. “That’s because we’re making them in small numbers. But we are looking at consumer pricing in the longer run,” says King.

The early adopters were mainly large enterprises and organizations. A popular use case is experiential marketing. One of the first major sales of the Rovr was to Nissan for its Paris road show in 2014. Dominator has been using it to show yachts to clients before actually building them in a customized way.

Now a new version of the Rovr, weighing 25 kg and collapsible for easy shipping, is aimed at a broader market.

VR gaming arcades are an obvious target. King thinks Asia will take the lead in VR adoption, just as arcades popularized video games. “People’s first experience of them will either be in arcades – that is, out-of-home entertainment – or in your business activity.”

See: Virtual reality cinemas join arcades in China’s offline VR boom

The key to many uses of VR is its level of immersiveness and how long you can be in it without getting exhausted or feeling sick. Rovr tries to achieve that not only by sliding but also by avoiding VR short-cuts like teleportation.

“For instance, if you’re wearing an HTC Vive headset and you’ve got room scale, you can’t walk beyond the room. If you want to walk beyond your room, then you have to teleport. Well, that’s not normal. You don’t normally teleport in real life. So that breaks immersion,” explains King.

“Those types of tricks will not solve the problem of full immersion as well as simulation sickness. The only way you can really solve that is to do what your brain is expecting. So, if you’re going to walk 25 meters, you might as well walk 25 meters. When you move your legs backwards and forwards, the brain accepts that as walking.”

Will this be the year of VR?

Wizdish co-founders Julian Williams and Charles King. Photo credit: Tech in Asia

The sliding idea actually dates back to 2001, when King’s co-founder Julian Williams first used it in a game for a BBC TV program. “I spent nearly ten years just getting the idea patented,” says Williams. “For me, VR is all that physicality. The more you move your body the more the brain thinks it’s actually happening. And that’s what I’m after.”

King, who has a PhD in materials science and worked in the semiconductor industry, came in to help build the prototype and the business. The friction between the shoes and the trackpad had to be reduced; how you moved in the VR world had to be proportional to normal walking. But the biggest challenge is consumer adoption.

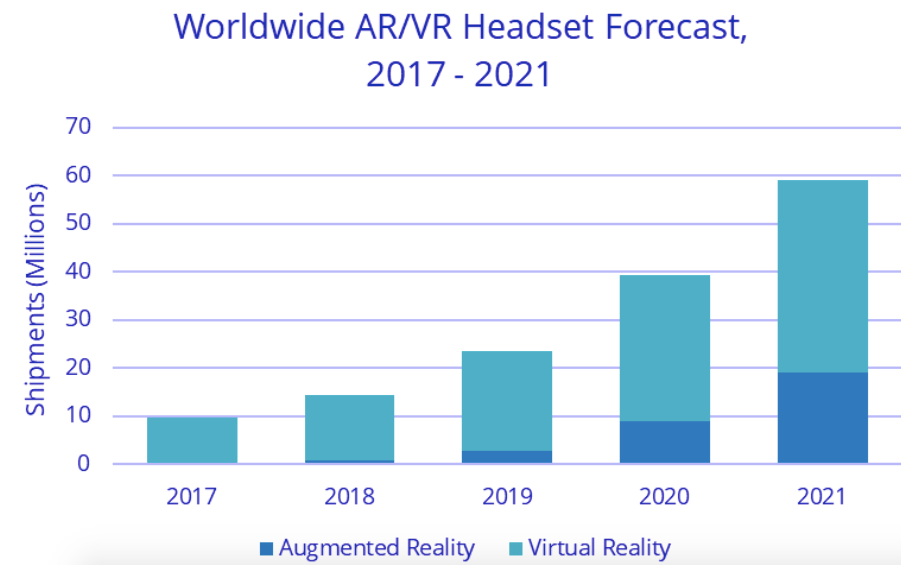

Virtual reality remains on the periphery of the consumer market despite the attention it has received since Facebook’s acquisition of VR headset maker Oculus in 2014. IDC data shows 9.6 million VR headsets were shipped in 2017. Most of them were low-power ones, like Samsung’s Gear VR and Google’s Daydream, that work with mobile phones but can’t provide full-blown VR experiences like those you get from headsets linked to PCs or game consoles.

Source: IDC

The number of high-end headsets like those from Sony, HTC, and Oculus were just 3.4 million. To put that into perspective, Nintendo alone sold over 10 million of its new Switch video game consoles last year.

Williams remains convinced, however, that VR’s time is around the corner, as the industry resolves issues with hardware and content. “I watched the internet happen, I watched phones happening, and I know this is going to happen. It’s a little bit like saying back in the days of black and white television, ‘Do you think colored TV will take off?’ There were always a few people who said ‘no’ because they were afraid of having to spend too much money on it, but the reality was that it was bound to take off. It’s the same with VR.”

See: 18 new books for entrepreneurs to get ahead in 2018

The major tech companies seem to think so too, judging from their big bets on AR/VR technology:

- Facebook’s acquisition of Oculus for US$3 billion.

- Apple’s ARKit in iOS 11 that lets developers build augmented reality apps for the iPhone.

- Google’s ARCore that provides similar support for building Android apps.

- Microsoft’s Mixed Reality VR platform is built into the latest version of Windows 10.

- Amazon is expected to unveil Alexa-powered AR glasses at CES next week.

But what will really give VR a boost is a better experience. And that’s where innovations like a more realistic and less sickening way of moving about in the VR world will play a vital part.

Startup Festival covered the travel and accommodation fees for this writer to attend their event in Seoul.

This post Why sliding – and not walking – is the future of VR appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/wizdish-rovr-mouse-for-vr

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment