Quoine co-founder and CEO Mike Kayamori. Japanese-Singaporean startup Quoine’s QASH token sale was Asia’s largest ICO in 2017. Photo credit: Quoine

Token sales, crowd sales, initial coin offerings (ICOs). Call them what you will, but they were 2017’s biggest tech trend. By working mainly with blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies, startups sold tradeable, cryptocurrency-like digital tokens. In turn, this enabled them to raise billions of dollars in funding via ICOs without turning to traditional venture capital.

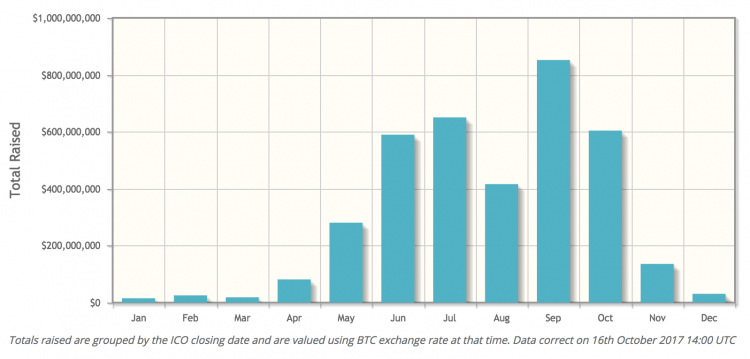

By June, token sales had overtaken angel and seed VC funding for the first time, netting more than US$550 million for coin issuers compared to the US$300 million raised from VC investors that month.

With such huge amounts of money moving in the ICO space – much of it involving buyers and sellers outside the ambit of accredited investor and securities trading rules – it was only a matter of time before regulators would step in.

Source: CoinSchedule

A core issue is whether coins distributed in ICOs represent a security interest in the organization that issues them, or function as simpler utility token that grants holders some form of access to the issuer’s products and services.

There are also concerns that ICOs are fertile ground for scams, while the cryptocurrency market more generally might serve as a safe space for crime syndicates, terrorist groups, and money launderers to conduct illicit business.

Watchdogs in the Asia-Pacific region have considerably varied approaches to ICOs, from implementing blanket bans to urging caution while continuing to allow sales.

<h2>China</h2>

The People’s Bank of China effectively banned ICOs in September, taking the world’s biggest market for token sales out of the picture.

In addition to stopping future sales and halting ongoing events, the central bank’s directive also ordered all completed ICOs to liquidate and return funds to investors. Progress on these last points remains unclear.

Bitcoin and ether – the two cryptocurrencies most widely used to buy ICO-issued tokens – crashed in value by 11 and 16 percent, respectively, after the bank’s announcement.

People’s Bank of China headquarters, Beijing. Photo credit: Max12MAX / Wikimedia Commons

<h2>South Korea</h2>

South Korea followed China’s lead in September, when its Financial Services Commission (FSC) banned fundraising activities involving cryptocurrencies. The agency also promised to impose “stern penalties” for organizations found to be running ICOs.

On a related note, the FSC (https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-southkorea-bitcoin/south-korea-to-impose-new-curbs-on-cryptocurrency-trading-idUSKBN1EM05K)”>indicated last week that it would introduce stricter rules for trading digital tokens and cryptocurrencies. It may also close some cryptocurrency exchanges operating in the country.

The FSC claims that prices of virtual currencies are significantly higher on South Korean exchanges compared to those in other countries. In addition, it has announced measures to tax capital gains on tokens.

<h2>Japan</h2>

Japan has been comparitively permissive, accounting for around 63 percent of the world’s bitcoin trading volume and recognizing the cryptocurrency as legal tender. In September, the country’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) granted 11 companies approval to operate cryptocurrency exchanges.

Looking more closely at ICOs, Japanese officials have said they have no plans to regulate the fundraising format. However, some commentators have cautioned that this does not necessarily mean Japan will become a safe haven for businesses looking to launch token sales.

“[Regulators] are just more tentative,” Koji Higashi, co-founder of crypto-wallet IndieSquare told Forbes recently. “They’re just trying to figure out if it’s going to be good or bad. It doesn’t mean they won’t start regulating more heavily in the future when problems start emerging.”

<h2>Singapore</h2>

MAS headquarters in central Singapore. Photo credit: Tech in Asia

In August, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) issued its first guidance note on ICOs, observing that “the function of digital tokens has evolved beyond just being a virtual currency” to the point that some coins “may represent ownership or a security interest over an issuer’s assets or property.”

As such, sellers of tokens with these characteristics are required to register a prospectus with MAS prior to their ICO. Along with secondary market operators set to trade the tokens, these sellers are also subject to Singaporean licensing requirements for securities vendors and need regulatory approval from MAS. This closely follows the line adopted by the US Securities & Exchange Commission.

In November, MAS issued a follow-up https://www.techinasia.com/mas-ico-general-guidance”>paper reiterating that it will regulate ICOs resembling equity and debt offerings, but also outlining exemptions for certain token sales of lower value.

<h2>Other markets</h2>

Indonesia’s central bank said recently it would ban all cryptocurrency transactions, presumably rendering ICOs obsolete in the country.

Neighboring [Malaysia](https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/malaysia-to-enforce-cryptocurrency-regulation-in-2018-9428242) has adopted a somewhat softer stance, indicating that beginning this year, the trading of cryptocurrencies and digital tokens will fall under the purview of securities regulations.

Regulators in Thailand and Australia have issued guidance similar to that of their counterparts in Singapore and the US, taking a hands-off approach while urging prospective buyers to be cautious and stressing that certain tokens may be subject to securities trading rules.

Taiwan has decided against outrightly prohibiting ICOs and is seeking to develop a regulatory framework around the format instead.

<h2>Up next</h2>

It is clear which markets are shaping up as Asia’s ICO hubs. But it’s still too early to determine how these more open jurisdictions may end up regulating token sales, says Philipp Pieper, co-founder and CEO at US-based fintech startup Swarm Fund.

“If you’re surprised that regulators are stepping in, you haven’t done your homework,” he tells Tech in Asia. “It was not unexpected – it was inevitable. I don’t think [the ICO model] will go away, but it will become much more regulated.”

Pieper, who previously had compliance-related roles with Allianz and Deutsche Bank, thinks that token issuers will also self-regulate as prospective buyers learn more about the format and the technologies that power these product offerings.

“It’s similar to the early 1990s when we had a vague understanding of what the typical internet user will eventually look like,” he says. “With that, the ICO might change in that it will become something where [issuers] have to invest early on into development of products, they have to prove their product is viable, and that consumers are already using it.”

Daniel Saito speaking at Tech in Asia Tokyo 2017. Photo credit: Tech in Asia

In this sense, ICOs may also become increasingly helpful in attracting investment via the more traditional VC route. More token sales may act as gateways to institutional fundraising as the new year unfolds.

Daniel Saito, director at startup consultancy RedRobot and a cryptocurrency expert who has worked in tech roles at NTT Docomo and Sega, explained why this may become more common while speaking at Tech in Asia Tokyo 2017 last September.

“It is a good validation from the actual masses – the traction, [VCs] can actually have access to Slack and Telegram groups, and see the sentiment the public has for the products,” he said, referring to typical channels that startups use to communicate with token buyers. “It gives them a feedback loop.”

This appears to be the tack pursued by TenX, a Singapore-based crypto-wallet startup that closed one of last year’s largest ICOs.

“We thought about doing a proper series A first. We decided to flip it around, do a token sale then a series A,” co-founder and president Julian Hosp tells Tech in Asia.

“Something interesting to [VCs] is we don’t need their money so much – we want partnerships,” he says. “That was our strategy – get a lot of buy-in from truly loyal fans, [sell to] 20,000 token holders that have a vested interest, and now we can go to traditional funds [where] we value the strategic partnership they can bring.”

This post 2017 was the year the ICO came to town. Here’s what’s in store for 2018 appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/2017-icos-2018

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment