Amazon India’s largest ‘fulfilment center’ in Hyderabad. Photo credit: Amazon.

A string of docks line one end of Amazon’s 400,000-square-foot fulfilment center in Shamshabad, near Hyderabad in southern India. Trucks from sellers back into the docks, unloading boxes after boxes of goods.

I am at the start of the loop where Amazon India’s staff takes over. Boxes are unpacked, then each product is weighed, tagged, re-boxed, and sent to a coded shelf from where it’s retrieved when you or I click the buy button on our screen.

With a storage capacity of 2.1 million cubic feet, this is the largest of Amazon’s warehouses in India – the company dubs them fulfilment centers.

At what tipping point between automation and manual does it make sense to put a lot of Kiva robots here?

What strikes me is the number of hands tagging, sorting, weighing, and moving products. This is Amazon, renowned for its early push into automation right from the acquisition of Kiva Systems, a pioneer in warehouse robots, for US$775 million in 2012. We read in awe about its experiments with AI and computer vision for a fully automated offline “store of the future.”

But there are no robots here. Its biggest warehouse in the giant Indian market is human-centric.

Amazon India VP Akhil Saxena is taking me on a tour of the facility where I feel I could easily get lost among the winding conveyor belts. It is in fact less than half the size of a typical Amazon warehouse in the US, he informs me.

“We started off in India with smaller buildings, and as we scale up the buildings, we are adopting in the right level of automation,” says Saxena. “If you want to bring in all the US automation, then the buildings have to be much larger. Our US buildings are typically one million square feet. There it makes sense for the product to move rather than the person, as you’ve seen in Kiva videos I’m sure where the person is standing and the shelf moves to the person.”

Amazon India VP Akhil Saxena. Photo credit: Tech in Asia.

Jeff Bezos committed US$5 billion to Amazon India last year, determined to win the next big market after failing to make headway in China. A chunk of that goes into price wars with heavily funded rivals like Tencent-backed Flipkart and Alibaba-backed Paytm, both of which have also raised billions from Japanese giant SoftBank.

From the very outset in 2013 when Amazon entered India, it has taken the long view, spending heavily not only on discounts but also in solving India’s biggest challenge: logistics. It has built up 41 fulfilment centers around the country – twice as many as its main local rival Flipkart.

At the same time, it’s not a one-size-fits-all model for the global ecommerce giant. The Indian arm has the necessary leeway to work out its localization strategy. Part of that is to minimize costs, and the millions of dollars it is losing in the battle for India. The conspicuous absence of robots is one manifestation of being local, although, ironically enough, the local player Flipkart – flush with US$4 billion in funding this year – has already deployed warehouse robots made by Indian startup GreyOrange.

“In the US, the labor cost is very high – US$15 to 18 per hour – but the capital costs are low, because the interest rates are also very low. In India, the capital costs are high, the labor cost or the variable cost is relatively lower,” continues Saxena. On the wall facing us is a big poster listing Amazon’s global work tenets. “So, the arbitrage is to say at what tipping point or at what ratio between automation and manual does it make sense to build a very large building and put a lot of Kiva robots here.”

An Amazon fulfilment center in Hyderabad, India. Photo credit: Amazon.

Lost and found

India has a federal structure with 29 states, each with its own rules and taxes. That’s one reason for having multiple warehouses in different parts of the country, apart from the logic of being closer to sellers and buyers in such far-flung corners like Ladakh in the Himalayas and Lakshadweep island in the Arabian ocean. Ladakh is the world’s highest delivery station for Amazon.

The rollout of GST this year aims to centralize a lot of the taxes and ease the movement of goods across states. That gives an incentive for larger warehouses to serve multiple states and gain economies of scale. So we may well see the Kivas in India soon, because warehouse robots bring artificial intelligence for real-time inventory management and order fulfilment – not just more efficient, error-free storage and retrieval.

Amazon staff at the fulfilment center in Hyderabad, India. Photo credit: Amazon.

But automation and how to calibrate it for cost tradeoffs is just one piece of the logistics puzzle in India. Finding addresses is another one. “Behind the Ganesh temple” or “near the water tank” is the sort of qualifier you’re likely to encounter because Indian cities rarely fall into a neat grid and a house number is only a hazy clue to its location.

One thing I’ve observed living in Bangalore is that I rarely get calls from Amazon delivery people with interminable questions on how to get to my place, like I usually encounter with other food, transportation, and shopping companies. It’s nice when deliveries just arrive on your doorstep without interrupting your work from half-an-hour earlier.

Saxena explains that a clustering technology fine-tunes the GPS coordinates of an address with each successive visit based on information relayed back from the delivery person’s device. So, after a few visits, it can pinpoint the location much more accurately for a regular customer. As for the vague addresses, Amazon introduced a landmark text field on its Indian app and site to capture that “near police station” extra information.

Amazon’s presence in India actually predates the launch of its ecommerce site. It had a development center in India to leverage Indian tech talent for building software products used on its platform around the world. So it has more local knowledge on India than observers sometimes give it credit for.

See: 25 failed startups in India and what you can learn from them

It combines its tech prowess with local jugaad, an Indian term for a sort of hack. For example, everywhere in India you find kirana shops (small stores). Amazon has been partnering with them for deliveries under an ‘I have space’ program. Tea stalls, beauty parlors, anybody with some space to spare can join in and earn a few bucks to serve as a hyperlocal pickup point. Today, Amazon has 17,500 such spaces in 225 cities and towns across the country.

Another Indian jugaad is its ‘service provider program.’ Apart from the big courier companies like Bluedart or its own Amazon Logistics, it uses small service providers for local deliveries. The service provider could be a housewife or a retired army colonel and Amazon trains them to make the deliveries in their locality, employing delivery persons depending on the volume of business. There are 350 such “entrepreneurs” currently, says Saxena, and two of them employ only women to deliver the packages.

For Amazon, it’s like having 350 offline stores without actually investing in them. And it has the added benefit of personalization, like that of a mom-and-pop neighborhood store.

You can call up the local service provider for that shampoo you forgot to order in time and have it delivered in half an hour if it’s in stock. And for regular orders from Amazon, the SP, as the service provider is called, knows your address, when you’re likely to be home, and the neighbors who don’t mind holding your packages for you. And if you only have a 2,000-rupee note, the SP can just adjust the change next time.

Such initiatives have contributed to Amazon now getting two-thirds of its orders from interior India beyond the major cities. At the same time, cross-border ecommerce has also picked up. Customers in India can easily buy products tagged Amazon Global without worrying about import duties or customs clearance which are taken care of. Conversely, Amazon now has 26,000 sellers from India on its global marketplace.

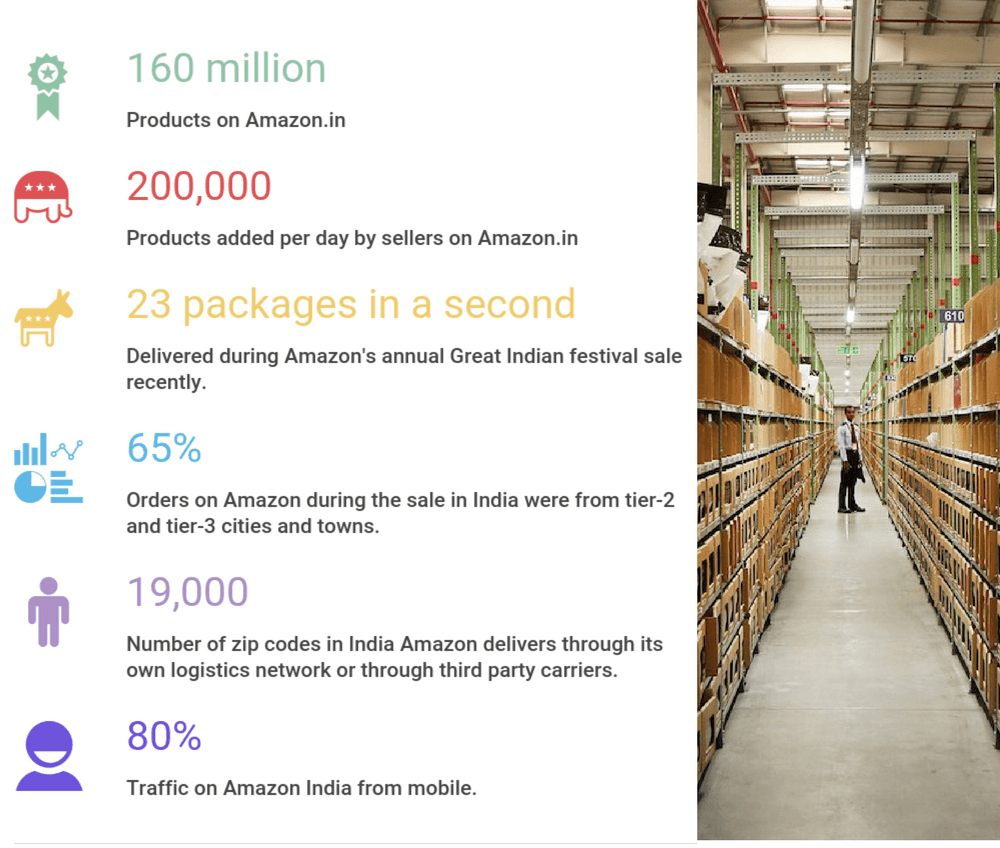

Source: Amazon; chart by Tech in Asia.

From CoD to PoD

Payment is the other big bugbear for ecommerce in India. Many choose not to pre-pay online even if they can, because of lack of trust or the anticipated hassle of having to follow up if a lazy delivery person doesn’t show up or gives up on a hard-to-find address.

India was the first market where Amazon adopted cash-on-delivery, even though it adds to logistics costs for processing payments as well as dealing with higher chances of returns. But it keeps tweaking payment options to nudge customers to go digital. Apart from the usual carrots for pre-payment, it has introduced a “pay on delivery” option.

So Amazon mails a link to the customer right after a delivery is made. The payment can thus still be made digitally instead of giving cash to the delivery person. And this doesn’t require a PoS device either for a card swipe, because clicking on the URL in the email takes you to a payment gateway.

The Indian government has also been pushing for digital payments. Amazon got a license for a digital wallet from India’s central bank, so customers can store a certain amount in it for quick, hassle-free payments. That was also a first for the American company.

It has been a steep learning curve for Amazon from the time it entered India and was forced to adopt a marketplace model because of restrictions on holding inventories for foreign retailers. This has brought Amazon closer to the Alibaba model with a large number of brands and offline retailers selling on the platform, apart from its own Cloudtail and Appario subsidiaries.

See: Ex-VP of Alibaba Porter Erisman on clash of ecommerce models in Asia, costly mistakes

Amazon and its big rivals continue to adapt to this big emerging market, where smartphone proliferation and downward spiral of data costs are bringing millions of potential new customers online each month. Mobile now contributes 80 percent of traffic on Amazon India.

This post No robots, please, we’re Indian – the lowdown on Amazon’s localization strategy appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/amazon-no-robots-ecommerce-strategy

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment