About a month ago, I was in New York visiting a tech-savvy friend. The living definition of “early adopter,” his entire home is voice-controlled with Amazon Echo, from his lights to his air-conditioner to his dishwasher. He seems to have a detailed opinion on just about every trend in consumer technology, and at work, he specializes in optimizing user experience for a fast-growing tech startup.

We have remained friends after meeting a few years ago in Beijing, when he was studying Chinese at Beijing Foreign Studies University. Since he returned to the United States, we mainly keep in touch through WeChat, but if it were up to him we would probably use a different messaging app.

Looking at the problem WeChat is having in its expansion overseas highlights broader trends that encompass Chinese internet companies when they globalize.

“The more I work in app design, the more frustrated I am using WeChat, because I keep noticing more and more flaws in it. Especially considering how many users they have, they really should offer a better user experience than they do,” he explained to me.

Indeed, he’s not the only one who has trouble using WeChat, and it has shown in the failure of the app to catch on with those who are not Chinese or communicating with Chinese people regularly.

For those of us who live in China, using it becomes so natural that we often don’t notice some of its flaws, like a fish that doesn’t realize it is swimming in water, since it has never left the river. But outside of China, WeChat is like a fish out of water. Here are a few of the key issues that may provide some insight as to why WeChat is struggling outside of the Chinese market:

Local storage

All message history in WeChat is stored locally on your device. This means that when you buy a new phone or log in to WeChat from a new device, your previous messages must be transferred manually. If your phone is lost or stolen, losing all that data can cause a real annoyance. WeChat claims that this is for privacy reasons, but that leads me to my next point…

Security, privacy, and transparency

Unlike many other messaging apps, WeChat does not provide end-to-end encryption. Instead, they employ transport encryption so that the message is encrypted between the user and WeChat’s servers.

When end-to-end encryption (e2ee) is used, the message is scrambled from the time it leaves the sender’s device to the time it arrives at the recipient’s, and only the recipient’s device possesses the digital “key” necessary to un-scramble the message. For messaging apps like WeChat that do not use e2ee, a second “key” is held in the company’s servers, allowing them to decrypt messages that use their platform. While even e2ee is not 100 percent unhackable, when it is not used, there is an additional point of vulnerability where the message’s security could be compromised. The more keys there are, the more ways there are for others to get in.

The lack of end-to-end encryption could make WeChat messaging more vulnerable to hacking for corporate or personal reasons.

What is perhaps more concerning is the lack of transparency from Tencent about issues of privacy and security regarding WeChat. In contrast, Facebook’s annual Global Transparency Report provides figures of the number of requests for information it has received from governments on a country-by-country basis, for the benefit of those concerned about surveillance. The figures relate to its products and services including Messenger and WhatsApp. Facebook claims to offer no “back door” into their end-to-end encrypted WhatsApp messenger, and despite public pressure from Brazilian authorities and the FBI, there has been no evidence to suggest that they offer such a “back door.”

Facebook has also been open about its use of Signal encryption protocol for both WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger’s “Secret Conversations” feature, an open-source protocol which is reviewed by cryptology experts. Facebook has published whitepapers as well, providing technical specification for how the encryption protocol is deployed.

In contrast, Tencent does not regularly publish a transparency report and does not have a policy of disclosing requests for personal information. They have provided little-to-no details regarding what encryption protocol they use for messaging, so it is nearly impossible for the average user to know exactly how secure their data is when using WeChat.

A recent update to the app’s privacy policy explicitly states that it will “retain, preserve, and disclose” users’ personal data to “comply with applicable laws and regulations,” indicating that Chinese security and law enforcement officials can likely gather private user data systematically and en masse. This is nothing new for most who closely follow the Chinese internet, and the governments of the US and other foreign countries are known to use social media apps for surveillance as well.

See: Chinese tech companies are feeling the heat from censors

What is possibly a greater concern is the security risk posed by outside actors. The lack of end-to-end encryption could make WeChat messaging more vulnerable to hacking for corporate or personal reasons.

And then there is the consistency of Tencent’s security claims themselves. On WeChat’s official site, it claims that due to their enablement of transport encryption and use of local storage, rather than their own servers, they are unable to view the content of users’ messages:

“WeChat securely encrypts your sent and received messages between our servers and your device ensuring that third parties cannot snoop on your messages as they are being delivered over the internet. We do not permanently retain the content of any messages on our servers whether they are text, audio or rich media files such as photos, Sights or documents. Once all intended recipients have received your message, WeChat deletes the content of the message on our servers and therefore third parties including WeChat itself are unable to view the content of your message.”

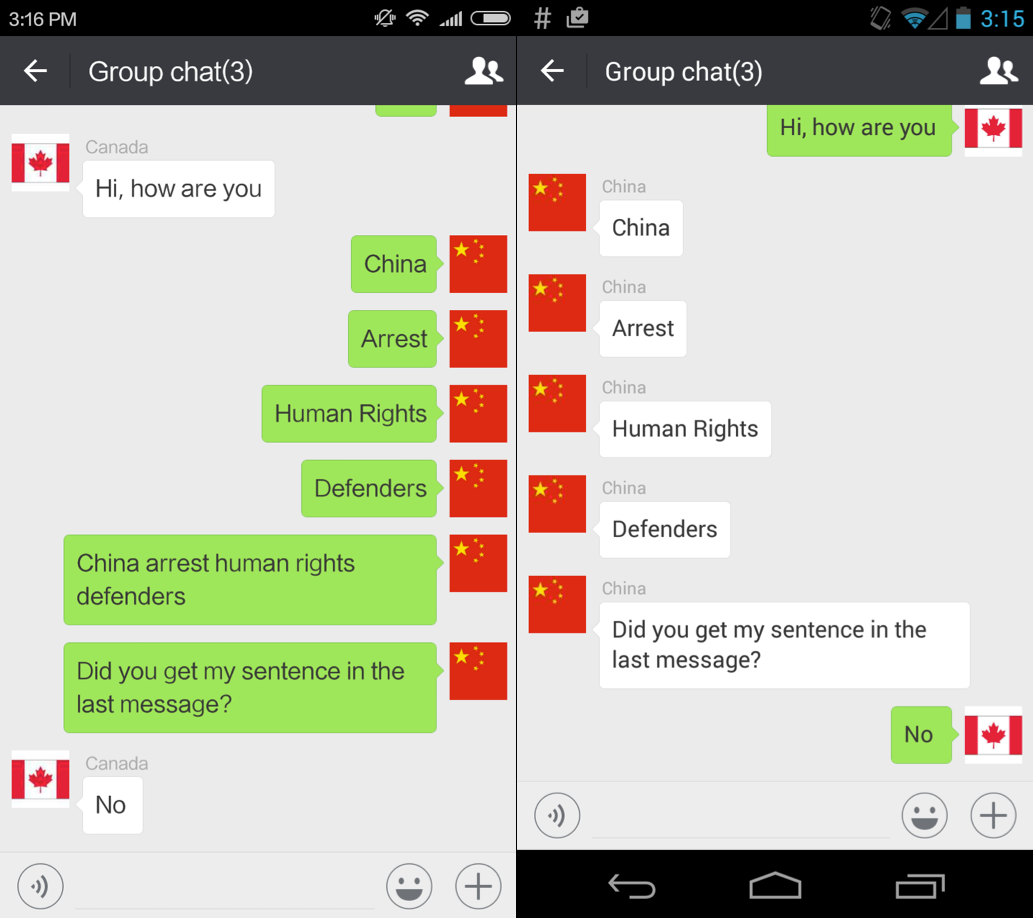

However, it is difficult to see how exactly this works. In an April 2017 report, the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab disclosed the results of a study which found that WeChat not only censored topics, but did so dynamically, in response to sensitive events. For example, they found that messages in both English and Chinese referencing a crackdown on human rights lawyers beginning on July 9, 2015 (referred to as “709”) were not sent to the recipient, with no notification given to the sender. If WeChat is unable to read the content of the messages, how are these messages deleted?

Recent regulations released on September 7 also officially made creators of online groups responsible for the content of their forums, and police disciplined 40 people in one group for spreading a petition letter and detained one man for complaining about police raids. If WeChat is unable to read and store the content of messages, how exactly does this happen? Are there whistleblowers in the group chats?

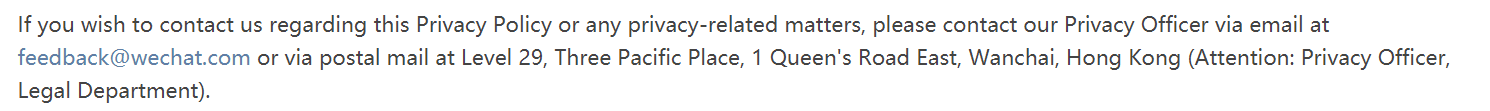

For those inquiring about their privacy and security policies, WeChat’s official site offers an email address for the office of a “privacy officer:”

However, if you try to contact that email address with any questions, you’ll receive an auto-reply like this:

When you try to go to that page, you’ll see a drop-down menu from which you can select a series of options to report or ask about, none of which refers to their encryption. You can report security violations or abusive content, but there’s no option to ask them about their policies.

When I submitted my questions, I never received a response. But it’s OK, I understand. They probably can’t afford to hire people to do this work. They only made US$6.2 billion in net profit last year.

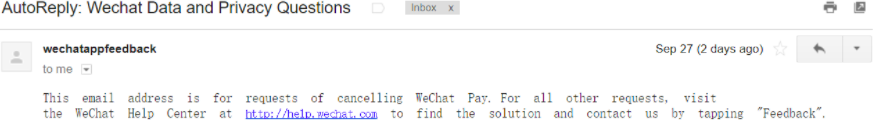

Its attitude towards privacy and security ranked them dead last, with a score of 0/100 in a 2016 report by Amnesty International evaluating the messaging apps of 11 top technology companies on their approaches to encryption and human rights.

Source: Amnesty.

With such a lack of transparency about privacy and security, it creates an information vacuum, to be filled by theories and rumors. It seems just about everyone I talk to in China has a different theory, or a piece of gossip about how the information they share on WeChat is surveilled, stolen, or otherwise used. This creates an atmosphere of mistrust around the app, where no one seems to quite know what information is vulnerable on the app that many of them use more than any other.

While the average person may not care much about security, techies like my friend do, and it’s usually by first reaching a critical mass of these users that an app can cross the chasm into mainstream use globally.

Localization

It’s one thing to lack support for certain features outside of the country and clearly indicate so, but in most parts of WeChat’s interface, they seem to just ignore the fact that people in other countries may try to use their app. Worse, when they try to make an effort, like supporting international credit cards, they add unsupported interface elements like a friend of mine encountered when trying to add a credit card.

While many Chinese people will sign up for public accounts under their own names in order to publish content to subscribed followers, this requires a Chinese ID card number, and therefore people who are not Chinese citizens are unable to register for personal public accounts. It is possible to create a corporate account for a foreign business by providing appropriate documentation, but even in that case, not all accounts are created equal. While Chinese public accounts can be viewed by both Chinese and non-Chinese users, foreign public accounts can only be viewed by non-Chinese users, making the vast majority of WeChat users inaccessible.

See: WeChat’s global expansion has been a disaster

In addition this, the ecosystem which supports WeChat so effectively within China is mostly nonexistent overseas. Few retailers outside of China accept payment via WeChat, and apps like Mobike, Ofo, Dianping, and Didi, which work so seamlessly with WeChat, do not yet have a strong overseas presence. Using WeChat outside of China is like putting a shark in the jungle: it simply doesn’t have the environment in which it is designed to thrive.

Other nuisances

Push Notifications: Wechat seems to only provide push notifications for new messages when the app is open, unlike apps like Facebook Messenger that alert you whenever you receive a message, regardless of whether the app is turned on.

This means that if you haven’t opened the app for a few days or since a restart of your phone, push notifications aren’t delivered reliably. For those in China, where checking WeChat is something people do constantly, this is less of a big deal. However, for those who use WeChat as a secondary or tertiary messaging app (like most non-Chinese WeChat users), this can mean going for days without realizing that they have received a message. On many phones this can be changed by adjusting the notification settings, but this is not something all users are aware of or think to do.

Lack of a “follow” vs “friend” option: For well-known or public figures who would like to use social media to reach followers who they do not know personally, Facebook and Linkedin offer a distinction between “liking” or “following” and “friending” or “connecting.” WeChat doesn’t offer this, so for those who would like to follow someone they don’t know personally, they either have to get their approval to add them on WeChat, or use Weibo, which has a lower number of frequency of users.

The 5,000-friend limit: For those who would like to use WeChat as a more public platform, they are limited to 5,000, hampering the reach of an individual account. While it seems like it could be an easy money-maker for WeChat to charge a fee for a higher contact limit, they do not offer this option.

Lack of embedded video: In the past few years, Facebook and Twitter have enabled embedded video into users’ news feeds, allowing users to watch videos as they scroll without having to click on a link and go to a separate site. This has been a catalyst of the pivot to video transformation currently underway among media firms. As of now, this pivot does not seem to be happening in China at the same rate, and this is likely because WeChat does not allow videos to be embedded and shared on “friends circles” very easily.

Final thoughts

Make no mistake: WeChat’s wide functionality within China is absolutely incredible. The app has revolutionized how people in China live their lives in only a few short years. As someone who lives in China, I use it more than anything else on my phone.

Looking at the problem they’re having in their expansion overseas, however, highlights broader trends that encompass other Chinese internet companies when they globalize: mainly, just how different the internet ecosystem is in China versus elsewhere in the world, and the widely different cultural and political expectations that global markets have for apps that play such an intimate role in their lives.

This post Opinion: Outside of China, WeChat is a fish out of water appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/outside-china-wechat-is-a-fish-out-of-water

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment