Photo credit: Gratisography.

In 1835, Charles Darwin went to the Galapagos, leading to his theory of evolution.

In the Galapagos, there are no predators. As a result, various kinds of species have evolved — the marine iguana, the Galapagos tortoise, the flightless cormorant, and the great frigatebird. The animals and birds there are bereft of the fight-or-flight syndrome that defines the animal kingdom. (Trivia: It is said the newly elected chairman of Tata Sons, N Chandrasekaran, went to the islands back in 2005 with his team members at TCS for a strategy offsite.)

When we think of Darwin, we think of the ‘survival of the fittest’, suggesting that the natural world is a boxing ring where the strong will vanquish the weak. It’s often used to justify the cutthroat competition in business, and even to argue that predators are needed in an ecosystem to keep its inhabitant fit. But, Darwin himself never used the term ‘survival of the fittest.’ It was, in fact, English philosopher Herbert Spencer who did so. The Galapagos Islands show that animals adapt to their surroundings. A protected ecosystem nurtures a different type of species.

What do we learn from the way nature evolves? Do we get the best outcomes for the world through ‘survival of the fittest’ philosophy, as is generally believed?

The question was triggered by concerns raised about capital dumping by large foreign companies to the detriment of Indian startups. It set off an intense debate in the Indian startup ecosystem. Some arguing that companies such as Amazon and Uber had an unfair advantage over their Indian competitors such as Snapdeal, Flipkart, and Ola. Others argue that this is the way free markets work — the strong will annihilate the weak — and any intervention by the government would only make things worse for the consumer at large.

See: India’s unicorns want government help to fight Amazon, Uber

Free markets and market fundamentalism

I have always wholeheartedly believed in the value of free markets until I started thinking about it more deeply. In our own lifetimes, we have seen free markets trumping economies that built walls around themselves. Those within those walls lost out to those outside, and they knew it. And when the walls fell — as did the Berlin Wall in 1989 — everyone celebrated. Yet, it’s important that we don’t get too ideological about free markets and insist on taking it to the extremes.

In What Money Can’t Buy, Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel makes a strong case for why we shouldn’t think markets can solve all problems. We need to be wary of market fundamentalism and our blind trust in the idea that only good will emerge when different entities fight it out in the market. Market fundamentalism can be dangerous, especially if some players come with an unfair advantage.

Market fundamentalism can be dangerous, especially if some players come with an unfair advantage.

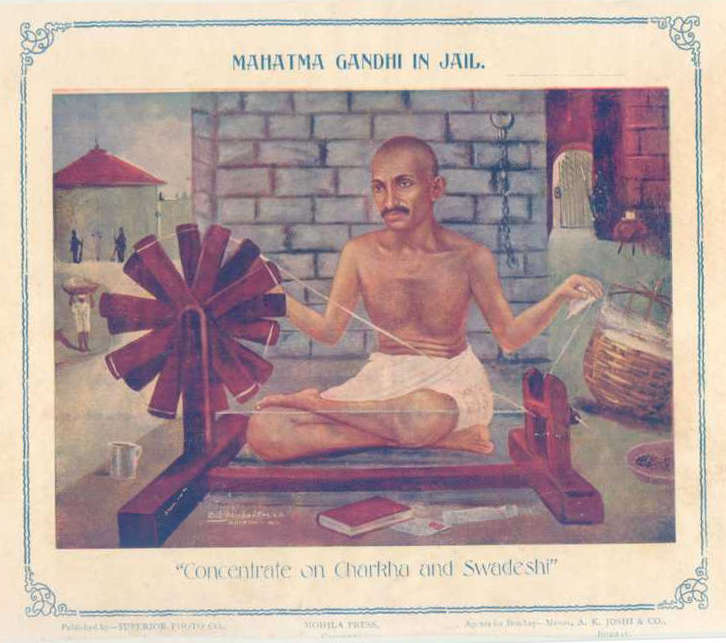

A poster for the Swadeshi movement. Photo credit: Wikimedia.

We can look at our own economic history: take the Indian textiles industry, for example. It has a long history stretching back to centuries (its admirers included Alexander the Great). Over the years, it developed a rich variety in terms of techniques, style, design, and material — not to mention a thriving economy around it. Yet, during the British era, the entire sector was pushed to the brinks of extinction by the machine-made clothes imported from England. Swadeshi, as a strategy, was a key focus of Mahatma Gandhi, who described it as the soul of Swaraj (self-rule). The resistance against such imposition became one of the enduring symbols (the Chakra) of the independence movement. Swadeshi as a purely economic measure for the growth of Indian industry is an important legacy to remember even in today’s times.

Breaking monopolies, building businesses

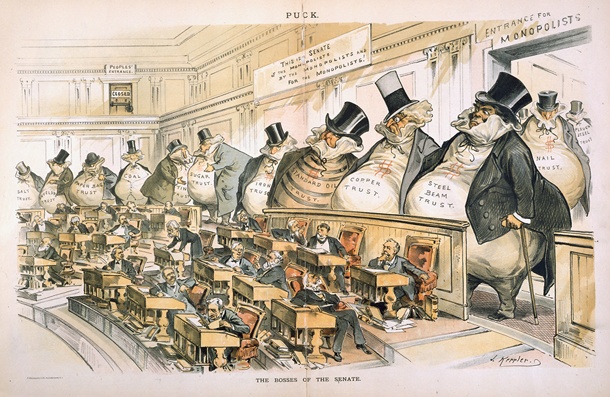

The Bosses of the Senate, by Joseph Keppler. Photo credit: Wikimedia.

The idea that monopolies are bad for an economy is not so radical. It’s well-accepted across the world. In the US, Ma Bell virtually controlled the entire communication system of the country — AT&T provided the telecom service across the country, and all of the equipment. Its motto was “One Policy, One System, Universal Service.” A forceful argument was made that a single company providing nationwide service was a vital part of national security. Today about 20 years later, this argument seems ridiculous. Without the breakup of Ma Bell, the internet as we know it wouldn’t exist. Giants like Amazon, Uber, Google, Facebook, and Snapchat would not have been created. Breaking up the monopoly resulted in increased competition, and therefore better customer service.

Should Kunal Bahl or Sachin Bansal or Bhavish Aggarwal call for support for homegrown business? These are the entrepreneurs who took the risks, launched their businesses, set the standards, or provided the services that Indian customers were not used to. They rolled up their sleeves, hit the road, understood the unique needs of Indian customers, and offered their value propositions. They created the market. The first experience of a well-executed ecommerce experience for most Indians came from Snapdeal or Flipkart, and the convenience of hailing a cab from anywhere using an app came from Ola. Amazon and Uber weren’t around when these entrepreneurs were busy converting skeptics into customers.

Should Kunal Bahl or Sachin Bansal or Bhavish Aggarwal call for support for homegrown business?

Toward long-term viability

Being the first mover doesn’t give anyone the entitlement to own the market. But, what we see today is an example of how unregulated market can take away some of the benefits that free markets provide to the society. Unregulated markets can be anti-competitive, because they give some players an undue advantage. Take the case of Amazon, Uber, and OLX. They have access to unlimited finance — from the fact that they have successful business for many years in other geographies — and can use that to stifle competition in India by providing products and services that are economically unviable even to them in the long term (but a loss that they can take on, because of the cushion from their home markets).

While it might seem to be a good deal for the customers, it can be a bad deal for the country as a whole. These companies are operating on negative gross margin sales in India funded by positive gross margins abroad. Simply put, India has policies to protect milk, steel, and other commodities from anti-dumping. If you want to import a foreign car, you pay a hefty duty. Even service sectors like banks and insurance have specific norms to ensure the long-term viability of these industries. Today, every country needs to nurture and protect its knowledge economy and think about capital as commodity. Hence, much thought is required around how capital might also be used in a way conceptually similar to dumping.

The consequences of not providing a policy response may include:

Modi’s Startup India Standup India initiative is unlikely to succeed

India’s startup ecosystem won’t take off if a dumping-like strategy can be used against Indian startups.

Take Micromax for example; its market share has fallen from 20 percent to 10 percent in just 20 months due to a dumping by MNCs. There is precedence in Europe: the market value of internet in the US is US$2 trillion and China is US$1 trillion (larger than auto, pharma, telecom), while in Europe it is only US$50 billion (1/40th of US, 1/20th of China). This alarming disparity is because China supported its firms (Google, Twitter, and Facebook were effectively banned), whereas Europe did not. I am not an advocate for bans, but it is an important point to ponder.

If India’s largest internet firms fail, millions of jobs won’t be created as a result.

Points to note: Chinese internet firms have created over 2 million jobs. In India OLX has 300 employees to Quikr’s 2,700; Uber has 1,500 employees to Ola’s 7,000; Whatsapp has 20 employees to Hike’s 500; Amazon has 24,000 employees to Flipkart and Snapdeal’s 45,000.

Allowing a dumping-like strategy could cause foreign investment in India tech to collapse

In China, after the government banned certain MNCs, foreign investment in the internet boomed (2004–2014: roughly US$200 billion) via investment into Chinese firms. Whereas, in Europe, after MNCs won in part due to a dumping-like strategy, foreign investment shrank (2004–2014: US$30 billion). This is because, after MNCs dominate in the internet sector, they require minimal additional capital. If a dumping-like strategy is used by MNCs, it scares away foreign investment into local firms.

The government will lose $400 million in annual taxes.

This estimate takes as inputs China taxation of internet firms of US$5 billion and Europe taxation of internet firms of US$1 billion.

What is the way ahead?

Is there a way to get the benefits of free markets and healthy competition while sidestepping some of the dangers they pose? This is possible by designing better policies.

First, these firms should be required to sell at positive gross margins and net take rates in India. Second, after a period of operating in India, a firm cannot fund-burn in India from operations abroad: like Indian firms, they would have to raise capital for the Indian entity from third parties. This ensures that at least some wealth creation accrues locally, which is critical to the birth of a tech ecosystem.

It’s often easy to take an ideological position, and argue that an absolute free market is the best solution to any economic issue. But the politically correct stand needn’t always be the correct stand for the long run. And in this case, we need to draw lessons from nature, history, and economics to arrive at the right solution. India has its local tech innovation future at stake.

It’s said, “don’t fix it, if it ain’t broke.” But, if we see signs of breaking, we better fix it. The Indian innovation economy needs to be nurtured and not nipped in the bud.

This post Should India adopt policies to level the playing field? appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/india-adopt-policies-level-playing-field-internet-companies

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment