On your bike: Hu Weiwei, Mobike co-founder and president. Photo credit: Mobike.

Driven by a persistent belief that consumers are willing to share necessities instead of purchasing them, China’s startups have been entering the “sharing economy” in segments ranging from cars to bicycles and even to umbrellas, basketballs, and battery packs.

China’s sharing economy growth is nothing to be sniffed at as it accounted for US$500 billion in transactions in 2016, with China’s government projecting it would account for 10 percent of its economic output by 2020. Bike-sharing company Ofo recently raised US$450 million at a valuation of over a billion dollars.

But is China’s sharing economy being oversold? The short answer is yes. The “sharing” economy in China is really just a rental economy on steroids and subject to the same constraints as rental businesses have been in the past.

With newer sharing economy startups like Ofo and Mobike, there is a single product owner who rents out physical products for its own economic gain. More established sharing economy startups like Airbnb or Uber, on the other hand, have multiple product owners and the economic benefits are shared among stakeholders.

Crucially, this results in bike-sharing companies bearing all the product costs and capital risks, which make a more brittle operating model than Uber’s where drivers bear these costs and risks. The goal for these startups is clear – monopoly. But their survival isn’t guaranteed.

The low prices being charged for renting these products dictate that they must scale rapidly and cheaply across a broad consumer base to achieve profitability, but the unit and market economics indicate this is unlikely at best. China’s sharing economy startups have three challenges in common – no sustainable competitive advantages, no network effects, and poor economies of scale.

No sustainable competitive advantages

A competitive advantage is a condition that allows a company or country to produce a good or service at a lower price or in a more desirable fashion for customers. These startups are essentially buying products and renting them out through an app that allows their products to be conveniently accessible. There is no evidence that they have created a competitive advantage through major product or process innovations that cannot be replicated readily.

To paraphrase Bobby Axelrod from the TV series Billions; what is it they do that they’re the best in the world at? Size is a poor moat as it is vulnerable to competitors that can easily match their spending. Tellingly, none of these founders can concretely explain how they intend to achieve profitability beyond “expansion.”

Little network effects

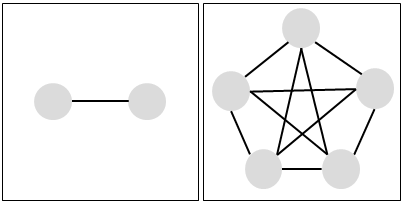

Network with two users vs network with five users.

The classic example of network effects is Facebook. With just two users, only a single connection is made, but with five users, each user can make four connections. Each additional user creates an exponentially increasing number of connections and hence more value (from positive externalities) to each user. So the more people use Facebook, the more valuable it becomes to existing users.

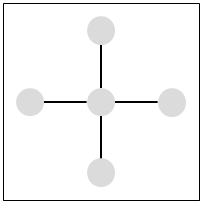

Traditional hub model

In the case of sharing economy startups like bike-sharing, adding additional riders to the system doesn’t increase the value of the network as the startup is the sole connection. Users are unable to derive value from connecting with each other. Reducing the value of participation and lowering the cost of non-participation. Further, the products still have to be distributed to places where users can find them.

It could be argued that bike-sharing startups enjoy network effects by having as many riders as possible to effectively serve as a distribution channel for the bikes. This assumes that riders will be riding from an area of high density to other places. The problem is that large numbers of riders use them during consistent times of the day such as the morning commute, result in them being “stockpiled” at a few locations and out of the reach of many of its users. This has been the case in China, where bicycles are concentrated at a single point and have to be manually redistributed across the city.

Poor economies of scale

These startups are hoping that in time they will become profitable by achieving the scale that enables large cost savings and sales volumes. While tech companies like Google and Facebook have near-zero marginal costs of expansion, bike sharing startups need to invest in more bikes to keep up with user growth. These bikes will also need to be repaired or replaced.

So, in order for sharing economy startups to turn profitable, two hopes must come true: their operating costs must fall, or they must increase their rental prices.

Few will ride a bike or play basketball in the rain, conversely, it’s unlikely that umbrellas will be rented when it isn’t raining.

Their operating costs are dominated by four factors – the cost of product, labor, land, and marketing. The cost of labor and land are determined by market conditions that they do not have any control over. In fact, bike-sharing startups are conveniently sidestepping the issue of paying rent for the land that their bikes are occupying.

Marketing costs are driven by a need to consistently match the marketing efforts of competitors, a need that is out of their control as none of them possesses a competitive advantage over the other. Product costs have a clear lower limit as these are not uniquely new products but generic ones that are hard to improve on for cost savings, with the suppliers having already found their market price.

To better understand this, think of toilet paper and how it could be improved or sold at a cheaper price.

The rental prices for these products are still relatively low due to heavy VC-funded subsidies in a bid to spur consumer demand and change consumer habits. A look at Mobike tells us how heavily subsidized these prices can be – each bike costs RMB 3,000 and is rented out at RMB 1 per half hour. Assuming it’s rented four times a day for half an hour each, it will take 1,500 days before breaking even. But with each startup stuck in a prisoner’s dilemma-esque race to the bottom, none will dare raise prices for fear of alienating riders.

More importantly, demand for these sharing services is seasonal. Few will ride a bike or play basketball in the rain, conversely, it is unlikely that umbrellas will be rented when it isn’t raining.

Musical chairs

China’s sharing economy is a massive game of musical chairs, with startups hoping they would land on the sweet comfort of VC funding when the music ends. As these startups aren’t public companies, they aren’t subject to market discipline and are only answerable to their backers, so it’s difficult to tell when the game will end. Meanwhile, the VCs are gambling to see who blinks first and when the game ends they hope they’ve backed the startup that monopolizes the market.

Even then, will the “winner” then be able to turn a profit? That depends on whether consumers’ habits have changed sufficiently to make “sharing” part of their lifestyles. It’s a gamble.

This post Opinion: Bike-sharing startups are just glorified rental businesses appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/opinion-bikesharing-startups-glorified-rental-businesses

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment