Photo credit: supernam / 123RF.

On a clear afternoon in Beijing last month, China’s small community of virtual reality filmmakers and animators gathered at Sandbox, one of the few VR film festivals in the country. Some of the world’s best VR films were on display: Oculus Story Studio’s Dear Angelica and Henry, Penrose Studio’s Allumette.

“Even though a lot of people [in China] discuss VR, most of them haven’t actually seen good pieces,” Eddie Lou, co-founder of Sandman Studios and organizer of Sandbox, tells me.

High-end headsets, like Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, can be too expensive for casual viewers, and many VR films are scattered across different platforms, he explains. “If they don’t have a deep understanding of the industry, they don’t know where to find the best stuff.”

China’s VR scene still suffers from a dearth of quality content.

Despite the hoopla around China’s VR industry last year – with some expecting it to hit US$8.5 billion by 2020 – the country’s VR scene still suffers from a dearth of quality content. That’s a problem Sandman Studios aims to solve, not only through its own animated short films, but by organizing regular VR film showings at Sandbox to inspire and entice Chinese artists, filmmakers, and game developers into the nascent industry.

“Right now, [creating VR films] is so difficult because you need to understand game engines, coding, and algorithms, but at the same time, you also have to understand how to tell stories,” says Lou.

“These two groups of people are actually separate – the animation and visual effects people and game developers. But because of this industry, everyone has to work more intimately together.”

A Sandbox attendee straps up for a VR short film. Photo credit: Tech in Asia.

China isn’t the only one with a content problem – VR experts worldwide have lamented the lack of a “killer app,” which is why Spaces, Facebook’s latest virtual reality hangout app, has caused such a furor online. Unlike other multi-person VR apps, Spaces takes socializing to another level by connecting users both in and outside of virtual reality. You can hang out in fantasy 360-degree environments with other avatar-ized friends, or call someone who doesn’t even have the app installed.

VR experts worldwide have lamented the lack of a “killer app.”

The VR content space is incredibly fragmented, with videos, films, and games spread across disparate platforms, such as Steam, Vive Port, Google Play, and Oculus Home. Currently, there’s no dominating platform, which means content creators have to publish their work on multiple platforms, or risk alienating users. It can also create compatibility issues across different headsets.

In China, video streaming sites like Youku and iQiyi have their own VR platforms. Brick-and-mortar virtual reality arcades, where users can pay less than US$5 to play games, are another distribution channel.

But the potential gains could be huge once the content becomes more convenient to access. Large tech giants, such as Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu, are all betting on the potential of virtual reality. And the thirst and willingness to pay for entertainment is certainly there – China’s movie box office is one of the largest in the world, clocking in US$6.6 billion in 2016 despite a slowdown in ticket sales. The country also leads the world in gaming revenue, and raked in US$24.4 billion in 2016.

Lou believes that China could see its own VR content heyday in the future – and wants Sandman Studios to be part of it from the start.

“Truly impressive companies all start as early-stage ones, like Lucasfilm, Industrial Light & Magic, and Pixar,” he says, referring to the years of research that Pixar underwent before starting to score big wins, such as the Genesis Effect in Stark Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. “But once the industry matures, then you get to set the standards.”

A screenshot from Free Whale’s video trailer.

Connecting dots

Lou is somewhat of an odd fish in the VR industry. He hasn’t specialized in software engineering, gaming, or visual arts. Instead, his background includes management experience at JD, one of China’s largest ecommerce companies, as well as consulting at Accenture and iResearch. In fact, it was after a two-year stint at APEC China Business Council, where he came in contact with different VR companies, that he decided to start Sandman Studios in 2016 with Jade Wai, the startup’s other co-founder.

“I had a lot of great contacts with overseas studios, a lot of connections,” he says. “So I wanted to be able to do a showcase in China, and let even more people watch truly high quality pieces.”

Lou is somewhat of an odd fish in the VR industry.

Those connections have helped Lou pull together many different pieces of the global and domestic VR industry. Not only is he organizing Sandbox, which happens several times a year, he’s also trying to bring international film festivals, such as Sundance and Tribeca, into China.

The ethos is similar to that of Sandbox: it opens access to some of the world’s most renowned virtual reality films, while potentially inspiring traditional filmmakers, artists, and game developers to jump into the space. For foreign film festivals, it’s a way for them to enter the Chinese market.

Lou is also leveraging his guanxi in the VR community to work with virtual reality cinemas, of which he expects 20 to 30 to open in China this year.

“As location-based centers, they really need content. But it’s quite painful for them to discuss terms with studios, one by one,” he says. “We’re already in contact with different studios, so we can help them in the initial discussions and create more distribution channels in China.”

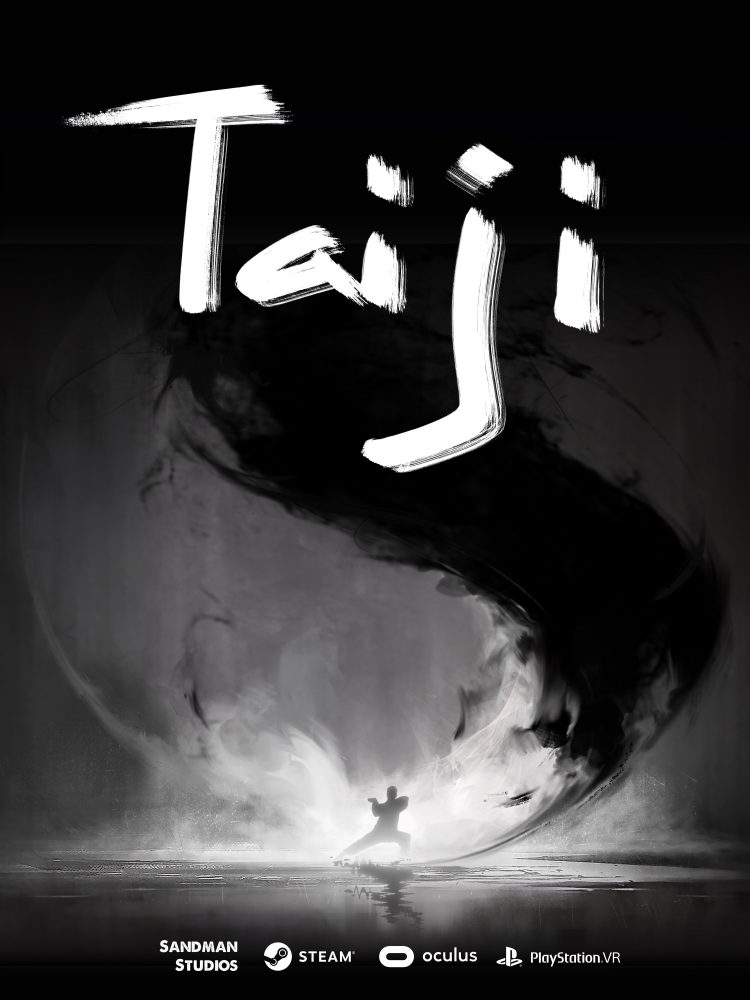

Concept art for Taiji, Sandman Studio’s first multi-person VR experience. Photo credit: Sandman Studios.

Sandman Studios is also creating its own narrative VR pieces. Its first short film called “Free Whale” is slated to launch this summer, though it’s more of an experimental demo meant to get the team’s feet wet when it comes to working with VR, says Lou. Like other VR studios, the startup has had to play with how it guides the viewer’s attention, as users can look at anything they want in virtual reality, not just where the director points the camera.

“Virtual reality has such a rich amount of [visual and audio] information,” he says. “So you have to use the environment to tell the story, not the camera lens.”

Users can manipulate ink and the air to mimic Tai Chi movements.

The startup is working on another piece called “Taiji,” a two-person experience about Tai Chi, a type of Chinese martial arts. The film will be styled after Chinese calligraphy, where users can manipulate ink and the air to mimic Tai Chi movements. It strikes an odd balance – not quite a game, yet not quite a story either.

“A story might have a beginning and an end – its narrative is very systematic. It has a pattern. But what we want to create for people is a type of experience,” explains Lou. “A story might be written to elevate the experience [in virtual reality], but the end goal of the product is not simply to communicate that story.”

Uphill battle

Lou has no illusions about the hard challenges ahead. He can map out the declining investments in VR and quantify the death of Chinese VR startups because in addition to Sandman Studios, he also oversees the research initiatives of Greenlight Insights, a US-based research firm wholly dedicated to AR and VR. He knows China’s VR content industry is in its infancy – and has the numbers to back it up. In 2016, for instance, a whopping 81 percent of total revenue generated by China’s VR industry went to hardware companies, not content.

That’s also why he’s so gung-ho about connecting different pieces of the VR industry.

“I really hope that more people go in the direction of narrative VR. The more people do it, the more valuable it becomes,” he says.

The Sandman Studios team. Photo credit: Sandman Studios.

Money, in terms of raising investment and generating revenue, is another key challenge for China’s VR content industry. “At the moment, even the best VR content will struggle to bring in profit and income to its developer team,” Lu Yihe, a VR-focused analyst at research firm iResearch, tells Tech in Asia.

Investments in China’s virtual reality industry have also cooled down since 2015 and 2016, she says. “That has put limits on the VR content market, which only just started during the second half of 2016.” However, once the method of charging for VR content matures, it’ll be able to monetize via IP, especially given how similar VR content is to traditional games, movies, and TV series, she says.

During a panel with VR filmmakers and animators at Sandbox in April, Lou led a discussion on the pain points in China’s VR film industry. Like Lou, the other panelists were both brutally honest about ongoing challenges – “We’re the only ones left,” joked Lei Zhengmeng, co-founder of VR animation startup Pinta Studios – while maintaining a surprisingly high level of optimism for the industry’s future.

When asked what the ideal length of a VR film should be, one panelist replied, “If you have tubes stuck in you, you can watch it forever.”

Luckily, we’re still far from a future of life support tubes and near-constant inundation of VR content. But as VR becomes increasingly accessible, and as games, movies, and applications improve, it’s not inconceivable to imagine a day when VR reaches YouTube-levels of distraction.

Currency converted from Chinese yuan. Rate: US$1 = 6.90

This post This startup is shooting for a Pixar moment in China’s fragmented but huge VR space appeared first on Tech in Asia.

from Tech in Asia https://www.techinasia.com/sandman-studios-profile

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment